|

From the end of the Civil War through the turn of the century, cotton production continued to increase dramatically as a result of several key developments. These included massive immigration from the deep South and Europe, removal of natives from prime cotton-growing areas, the invention of a new plow that more easily broke the thick black sod of the plains, the invention of barbed wire, the extension of railroads, the invention of cotton ginning (removal of seeds from cotton fibers and cleaning and baling of the lint), and perfection of cotton compressing at the side of railroads for easier shipping.

Clearly, "King Cotton" became a central feature of the Texas economy, attracting considerable investment capital, labor power, and technological development. Other industries within the broader agricultural sector also grew considerably in late nineteenth century Texas, including ranching, timber, and corn. Still, cotton was king until the 1920s when it began a decades long decline in importance caused by the drop in demand during the Great Depression, the loss of labor power during World War II, the rise of other centers of cotton production abroad, and federal efforts to hold down production to maintain prices.

As the railroads extended their reach in the late nineteenth century across the state to the panhandle and the high plains of west Texas, their influence grew. At first, the combination of more extensive railroad service and the relocation of cotton compresses from the seaports to rail sidings helped cotton farmers break the power of the port facility operators. But, hostility and political competition between farmers and ranchers on the one hand and the railroads on the other quickly grew.

Because railroads tend to be natural monopolies (in which the huge cost of investment makes it inefficient to have more than one service provider in a particular area), they tended to exercise enormous market power over their customers--the farmers and ranchers. The railroads' power to set rates was perceived as injurious to farmers and ranchers.

The struggle between railroads and their customers led to the victory of James Stephen Hogg in the gubernatorial election of 1890. Hogg ran chiefly on a populist platform whose main plank was the promise to regulate the railroads. In that same election a proposed amendment to the Texas constitution was ratified that permitted the creation of a railroad regulating body that among other things would regulate freight rates. Hogg made the first appointments to the new Texas Railroad Commission in 1891. Three years later in 1894 the Legislature made those positions elective.

The creation of the Railroad Commission represented the most significant and direct political clash between competing economic interests since the Civil War pitted slaveholding cotton growers against northern industrialists. Governor Hogg pushed through a series of laws, known as "Hogg's Laws," aimed at reining in the railroads, out-of-state corporations, and insurance companies.

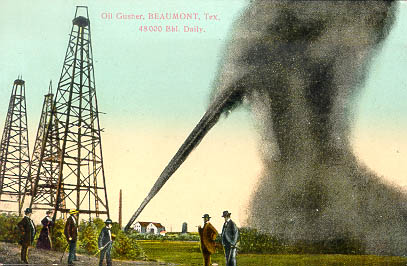

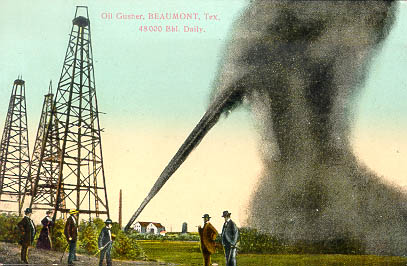

As cotton began its long decline in the early decades of the twentieth century, oil began to assume increasing prominence. Though commercial oil exploration had enjoyed some limited success in the post-Civil War era, the industry did not make major discoveries until the late 1890s and the first years of the new century.

As sizable discovery followed sizable discovery, a fully integrated industry began to take shape, including pipelines and oil refineries on the Gulf Coast. Then, as Henry Ford and other manufacturers turned the automobile with its the internal combustion engine into an object of mass consumption, the Texas oil industry came into its own. By 1929 there was already one automobile in the state for every 4.3 of the almost six million Texans. Also by 1929, the four states of Texas, Oklahoma, Louisiana and Arkansas accounted for approximately 60 percent of oil production in the United States.

The success of the oil and natural gas industry helped diversify the state economy, which until the first quarter of the century was still dominated by agriculture. The dominance of that sector by cotton continued, but to a lesser degree than in the earlier period. Cotton prices had tumbled, while new fruits and vegetables, harvested by increasing numbers of migrant Mexican workers, grew in importance. While white and black Texans also worked in the itinerant farm labor pool, Mexicans became the backbone of the industry.

|