The Misguided Democratic Hope, Republican Fear, of a Blue Wave Based on 2018 Texas Primary Turnout

The increased activity of Democratic partisans in the early stages of the 2018 Texas primaries, especially the increase in their early voting, has many seeing yet another sign of the much-heralded Democratic wave reaching Texas shores. And Democrats are not the only ones raising flags. Governor Greg Abbott sent an email to supporters this week which read, in part, “If these trends continue, we could be in real trouble come Election Day,” further noting, “Democrats are already on a winning streak, flipping seats in special elections across the country in GOP strongholds.” With both Democrats and the state's Republican figurehead predicting a Democratic surge, the political press can't help but follow suit.

But a closer examination of the relationship between primary voting and general election performance shows that Democrats might be wise to temper their expectations. While Texas Democrats may indeed perform better in the 2018 general election compared with their recent performances, historical election data from the past 20 years fails to display any clear relationship between primary participation and general election outcomes in Texas.

Assuming this connection implicitly makes a prediction about general election performance based on one or both of two assumptions of behavior. First, that higher Democratic turnout in the primary relative to Republican turnout is a reflection of a difference in enthusiasm that will result in better general election performances for Democratic candidates. This set of assumptions is operative when one notices the higher turnout of Democrats (either day-by-day, in key counties, or overall) relative to Republican turnout, and on account of this difference assumes a better general election performance for Democrats in November relative to past elections.

The second assumption is that higher Democratic turnout relative to previous comparable primary elections is a reflection of increased enthusiasm, and will, again, result in better general election performances. The second version of this assumption is operative whenever one compares 2018 Democratic primary turnout to 2014, notices the increase in voting, and assumes that this increase portends a better general election for Democratic candidates than recent attempts. Let's look at the implications of both of these sets of assumptions and see what the available data has to say.

Relying on daily early vote totals in the 15 counties with the most registered voters, as reported by the Secretary of State, many have noticed Democratic primary voters outnumbering Republican primary voters in early returns. In 2014, Republican early voting totals surpassed Democratic early voting totals on each of the 11 days of early voting. As of this writing, total Democratic early, in-person voting has surpassed Republican early, in-person voting in these counties in each day of voting so far save one.

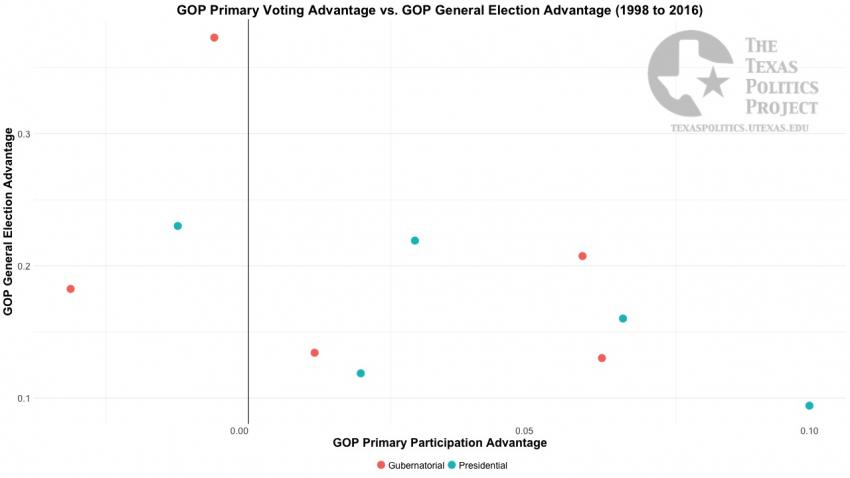

We can begin to examine whether or not higher Democratic primary participation relative to Republican primary participation leads to better election performance by graphically representing these two quantities against each other (as in the figure below). The horizontal axis displays the amount by which Republican primary participation outpaces Democratic primary participation among registered voters (i.e. the difference in the percent of registered voters who turned out in each of the Republican and Democratic Primaries),* the vertical axis represents the difference in the share of the two-party vote between the Republican candidate for President/Governor and the Democratic candidate (i.e. the Republican advantage). Since Republicans have won all of the elections in this time-frame, they always have an advantage, but what we’re interested in is whether or not differences in primary participation can explain any of the variance in the GOP’s general election advantage.

If there’s a relationship between these two quantities, then the points on the graphic should align in a distinct pattern. Specifically, if Democratic participation in the primary, relative to Republican participation, results in a better performance in the general election, then the points on the graphic below should cluster together in a linear fashion from the bottom left of the graphic to the top right (or, in English: as the GOP primary participation advantage increases, so too should their general election advantage, or, as the GOP primary advantage narrows or disappears – what we may be witnessing in this election cycle – so too should their general election advantage.)

Not only is this not the case, but it appears as though in the three elections in the last 20 years in which Democrats held a primary participation advantage (the points to the left of the vertical line: 1998, 2002, and 2004), in two of those cases (1998 and 2004) the Republican electoral advantage turned out to be larger than in any other election in the time series. The opposite of the prediction based on the first set of assumptions.

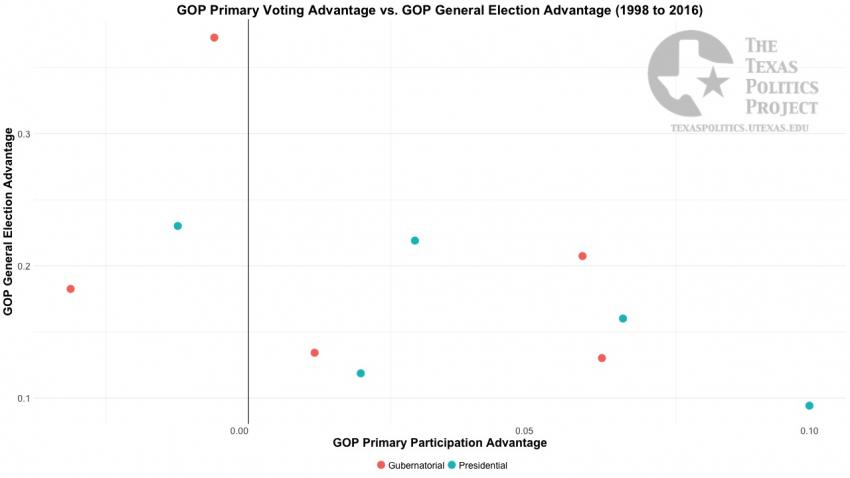

The second set of assumptions proposes that the increase in Democratic primary turnout compared with 2014 portends a better general election performance. That the excitement of partisans, as expressed through turnout relative to the last comparable election, is the appropriate measure of enthusiasm, and in turn, the better predictor of general election performance.

In this case, we still want to explain the variance in the GOP’s electoral advantage as measured through the difference in the share of the two-party vote, but now, we’ll plot the percent change in Democratic turnout relative to the previous comparable election (presidential or midterm) on the horizontal axis to see if a pattern exists. Visually, the results below paint a picture somewhat closer to the assumption. It appears as though there is a slight decrease in the Republican general Election advantage as Democratic turnout increases from one comparable election to the next (looking at the points from left to right on the graphic) – but the key word here is “slight.” While this relationship may look like it might exist based on a cursory visual inspection of the data, there is actually no statistically significant relationship between the two measures.

In summary, looking at elections between 1998 and 2016, there is no evidence of a relationship between partisan primary turnout and general election performance to speak of.

Before Texas Republicans relax and Texas Democrats sink back into their usual state of depression, a few caveats should be mentioned. While no statistical relationship is apparent in the data, increased Democratic primary participation is no doubt a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for improved general election performance. Additionally, the data that we’re examining here is a rather short time series (though an accurate representation of recent voting trends), and it could be the case that with more data, we might find a relationship (though we're skeptical). Finally, it’s hard to model the outcome that people have in their minds as they promote these results. They might be trying to justify an expectation of better Democratic performance, but in reality harboring an hopes of a (any) Democratic victory, when we have no occurrence of this latter phenomenon in recent history. This is all to say that while the relationship between primary participation and general election performance hasn’t existed in the past, this doesn’t mean that the increase in Democratic enthusiasm that people are imagining isn’t real, or that it won’t manifest itself this time around; it’s just not a conclusion that people should draw with such certainty from primary election turnout, let alone a few days of early voting returns.

* The benefit of looking at the percent of registered voters is that this removes changes that are a function of population increases by normalizing the quantities.

We encourage you to republish our content, but ask that you follow these guidelines.

1. Publish the author or authors' name(s) and the title as written on the original column, and give credit to the Texas Politics Project at the University of Texas at Austin (and, if possible, a link back to texaspolitics.utexas.edu, or to the specific subpage where the content resides).

2. Don't change the column in any way.

3. You can republish any multimedia (including, photos, videos, audio, or graphics) as long as you give proper attribution (either to the Texas Politics Project, if not already included in the media, and to the media's author).

4. Don't resell the column

5. Feel free to publish it on a page surrounded by ads you've already sold, but don't sell ads against the column.

6. If we send you a request to change or remove our content from your site, you must agree to do so immediately.