The Elephant in the Room: Texas Republicans Were Pretty Trumpy Before Trump

After four years of most major Texas Republican elected officials kowtowing to Donald Trump out of a mixture of deference and fear, Texas Republicans now seek paths for moving forward in his turbulent wake. They are in a different position than their national counterparts vis-a-vis Trump’s exit and how the experience of his presidency is to be incorporated into both the party’s identity and Republican elected officials’ political strategies. Trump has left the national party bereft, having lost the White House and presided over the GOP relegation to minority status in both houses of Congress (albeit narrowly in the Senate). But Republicans still reign in Texas, and are in a better position to navigate post-Trump politics than their national counterparts.

The key to understanding Texas Republican political leaders advantage is the fact that many invoked the central elements of Trump’s appeal in their rhetoric and policies – the unabashed resentment of the political and cultural legitimacy gained by people of color, the unbounded vilification of political opponents, a white nationalist view of American identity, the conviction that undesired electoral or policy outcomes are the result of incurably corrupt national institutions manipulated by uniformly feckless elites – long before Trump was a presidential candidate. Texas Republican voters respond positively to these themes, and, based on what years of Texas public opinion data tell us about their attitudes, a good chunk of them can be expected to continue responding to them even if Trump is not the one doing the articulating.

A generation of Texas elected officials know this from experience, and can be expected to continue sounding what we now think of as Trumpy themes, minus Trump himself. The early signs point to a collective effort to finesse the recent unpleasantness around Trump’s unwillingness to acknowledge the legitimacy of the election and his successful encouragement of others to act on these unfounded views. Trump's rhetoric in his final weeks in office yielded concrete support from Republican elected and appointed officials, including U.S. Senator Ted Cruz and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, as well as the members of the mob that ransacked the Capitol amidst an effort to hunt down members of Congress and the former Vice-President.

Not all Texas Republicans went quite as over the top as Cruz and Paxton in following Trump’s lead, but most of Texas’ Republican elected officials and opinion leaders have either declined to renounce Trump to the bitter end, or sought to change the subject as quickly as possible. Among the Texas GOP delegation to Congress, none voted for impeachment, which is perhaps not so surprising given the history of nearly uniform support for Trump among Republican voters throughout the entirety of his presidency. But 16 of them voted to question the Electoral College votes of Pennsylvania and Arizona *after* Trump supporters violently stormed the U.S. Capitol. Statewide Republican leaders not faced with having to take record votes related to Trump’s aiding and abetting the January 6 insurrection seemingly have been very interested in talking about other subjects (as in Governor Abbott’s pique at the screening of National Guardsmen for right wing militants among those deployed to Washington D.C. for the inauguration), or picking their spots for targeted criticism. Senator Cornyn sided with majority leader McConnell in declining to support Trump’s questioning of the Electoral College votes, then, like many other Texas Republicans, pivoted quickly on inauguration day to criticizing Biden’s new policy changes, particularly pulling the permit for the Keystone XL pipeline.

Going all-in on vilifying Biden’s specific policy turns is a reflexive response for Texas Republicans, particularly as the new president shifts toward reversing the climate and immigration policies of the previous administration. But the elephant in the room is that anti-democratic and nativist politics in the Republican Party of Texas predate Trump and, as the events of recent weeks make very clear, will outlast his presidency. Trump mobilized these impulses in a more direct and undisguised manner than any other successful national politician since George Wallace. His success in generating support among Texas Republican voters suggests just how deeply rooted these tendencies are in the state’s GOP, and, with or without him in the White House, Trump's success with GOP voters has left most Republican elected officials apparently unwilling to reject or even condemn Trump’s activation of anti-democratic forces lurking within the Republican Party. Even though Trump has damaged his own brand and that of the GOP with his refusal to accept his loss to Joe Biden without regard for the cost imposed on the stability of Constitutional institutions, the anti-democratic habits of thought and action he escalated are now part of the Republican mainstream.

We call these “habits” because Trump can’t be said to have promoted any reasonably coherent political philosophy beyond his own anti-rational cult of authoritarian personality. He provided policy and political wins to the Republican coalition that were of value to his coalition “partners” in governing – conservative court appointments and top-heavy tax cuts chief among them. But beyond some ill-founded beliefs about trade and nationalism, one doesn’t have to resort to psychology to note that Trump’s role has been nothing if not self-serving at its core, and nearly devoid of any programmatic ideology other than a relentless dedication to his self-interest, a solipsistic devotion to his own prejudices and predispositions, and a straightforward dedication to expediency as his basic principle.

The combination of these personality traits with a relentlessly combative mode of political operation enabled him to tap into a growing animus toward multicultural democracy and its norms of tolerance and constitutional balance that has long been brewing within the Republican Party. He released those forces and encouraged their public expression for the length of his time in the political spotlight, from the “build the wall” and “lock her up” chants of his heated campaign rallies in 2015 to his exhortations to the gathered crowd on January 6th at what would be the last of his beloved rallies while still a resident of the White House. The anti-democratic hostility he unleashed and legitimized now defines the worldview of many Republican voters and, increasingly, the representatives they are sending to gerrymandered legislative bodies. But Trump only amplified sounds that were already emanating from the GOP base. This was particularly true in Texas, where Trump elbowed aside Ted Cruz, who had already been attuned to these rumblings.

While this may seem like a harsh, even partisan, judgment, there is ample evidence of these attitudes among large swaths of the Texas Republican Party in public opinion polling conducted both before and during Trump’s term in office. Texas is an important site for assessing these attitudes in the GOP because it is a large node of ideas and politics in the network of conservative Republican politics in the U.S., and because, more proximately, high profile Texas Republicans have prominently declined to condemn Trump’s clear antipathy for the democratic process writ large and the Constitution in particular.

Trump’s embrace of baldly nativist beliefs was apparent long before he ran, and was central to his identity as a political candidate from the moment he spoke of immigrant rapists and murderers shortly after descending from the heights of Trump Tower via escalator to announce his bid for the GOP nomination in 2015.

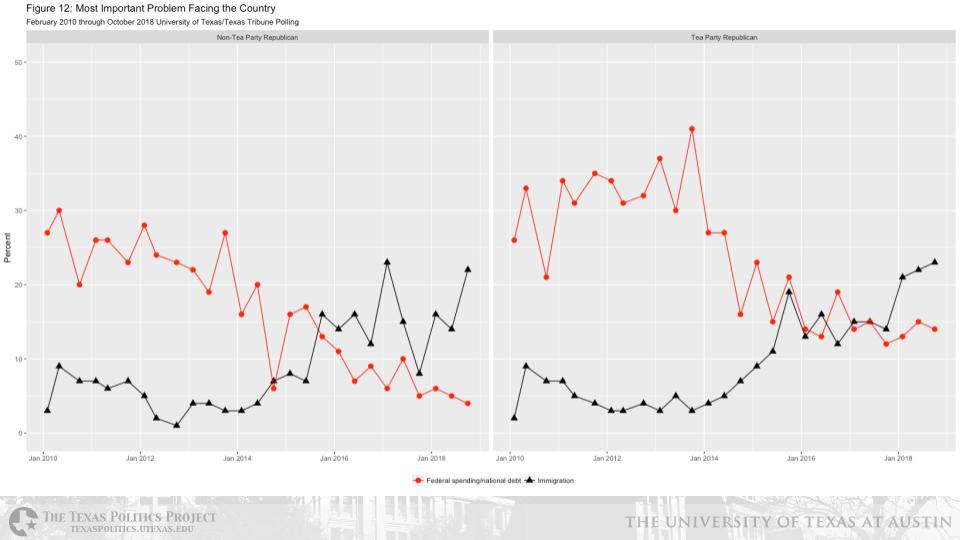

But the roots of the coarse nativism and race-baiting commonly associated withTrump were already well established in the attitudes of Texas Republicans by the time he mounted his run, particularly if we go back to the dawn of the tea party movement’s emergence as a force in Republican politics. Public opinion data clearly show that after a brief preoccupation with issues such as federal spending and taxes, the adherents of the tea party insurgency that surged in 2009 within a few years time became more focused on illegal immigration and the security of the border as their primary national concern.

(Source: University of Texas/Texas Tribune Polling)

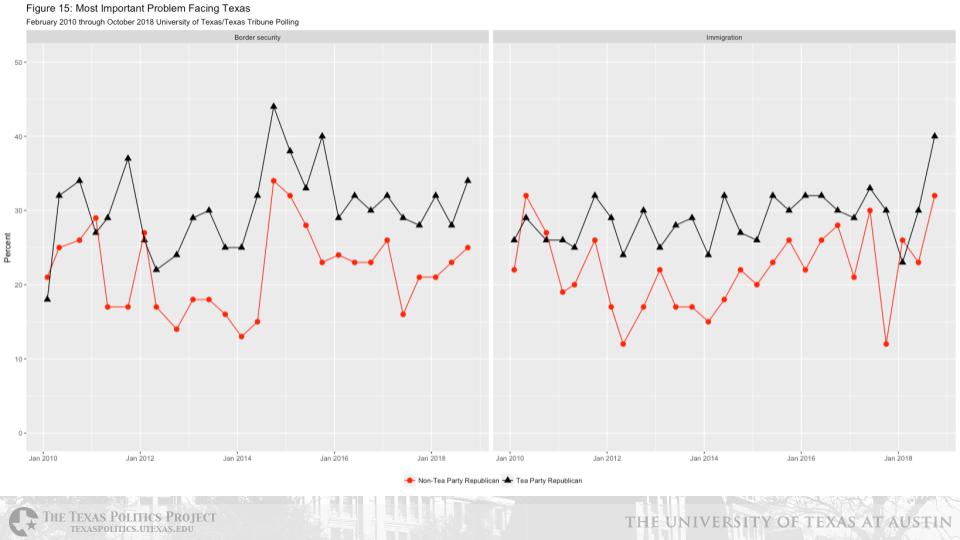

At the state level, border security and immigration were cited as the most important problems facing the state by large majorities of both tea party identifiers and non-Tea Party Republicans in Texas as early as 2010. Between 2010 and 2015, large pluralities or majorities of Texas Republicans embraced a series of measures that would later be central to Trump’s rhetoric, from revoking birthright citizenship, to the questioning of citizen status by police officers, to the immediate deportation of all undocumented immigrants in the U.S., to limiting the amount of legal immigrants coming into the country, to ending bilingual education.

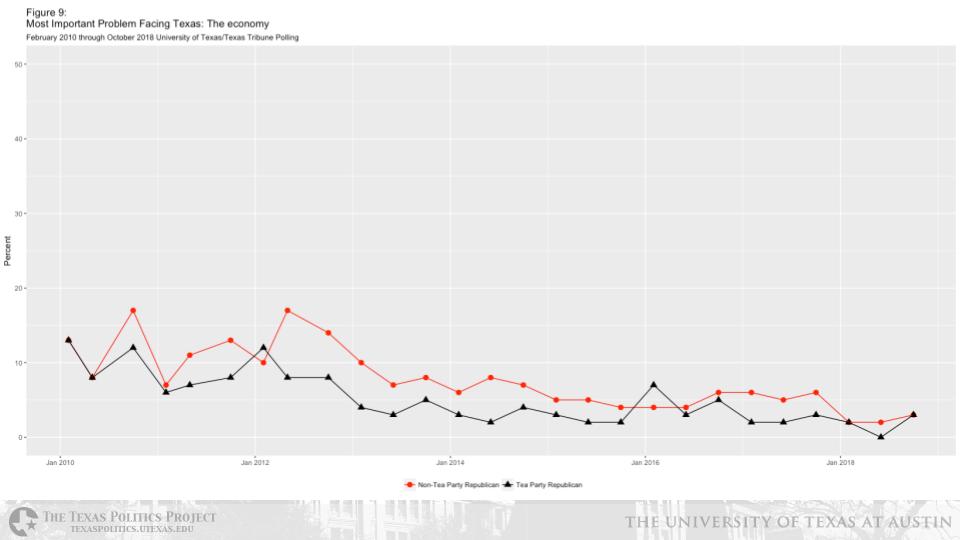

(Source: University of Texas/Texas Tribune Polling)

(Source: University of Texas/Texas Tribune Polling)

During the same period, these attitudes coexisted with an acute sense of racially-tinged cultural aggrievement among a sizable share of Texas Republicans. In the June 2015 UT/Texas Tribune Poll, prior to Trump’s entry into the primary race as what was then a dark horse candidate, asked about the discrimination experience by different groups in America, Texas Republicans indicated that Christians were the group that faced the most discrimination in America (as measured by the share of Republicans, 39%, who said they face a lot of discrimination), followed by whites (21%), and only then, Muslims (20%). Eleven percent of Republicans in 2015 said that African Americans face “a lot” of discrimination in America, nearly half the share that said the same of whites, and nearly a quarter of the share who said the same of Christians. By June of 2020, amid a Spring and Summer of protests and continuous coverage of America’s racial injustice, June UT/TT polling still found 28% of Republicans saying that Christians face the most discrimination in America, followed by whites (17%), and, only then, African Americans (16%).

Similarly, the willingness to view the election system as flawed (if not explicitly “rigged) was also evident. In the run-up to the 2016 Election, in October UT/TT polling, 53% of Texas Republicans said that votes being counted inaccurately would be an extremely serious problem in the upcoming election (another 24% thought this would be a somewhat serious problem); 59% said that people voting multiple times would be an extremely serious problem (24% somewhat serious); and, at the intersection of nativism and suspicions of the electoral system, 70% said that people voting who were not eligible would be an extremely serious problem (19% somewhat serious).

Given the apparent centrality of groups galvanized by conspiracy theories about secret cabals and the persecution of whites in counter-protests at racial justice marches and, more recently, in the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, it’s worth noting that such fever dreams were common among Texas Republicans. They surfaced in public in the spring of 2015 in the run up to a planned military exercise known as Jade Helm 15. Wild conspiracy theories (for the time) circulated about the exercise providing cover for a supposed military take-over of Texas. June UT/TT polling showed a Republican electorate willing to embrace the underlying tenets of the conspiracy: 54% said that it was either “very” or “somewhat likely” that the U.S. military would order martial law in Texas; 63% said the same of military arrests of political protesters; and 64% said the same of a military seizure of private property. Given this, it should come as no surprise that in the same poll a majority of Texas Republicans, 57%, supported activating the Texas National Guard to monitor the U.S. Military — this, despite the fact, that the military is the most favorably viewed institution among Texas Republicans. Famously, Governor Greg Abbott, in office less than a year at the time, seemingly validated these views by ordering the Texas State Guard to monitor the exercise to ensure that “safety, constitutional rights, private property rights and civil liberties will not be infringed,” per contemporary coverage by Jonathan Tilove in the Austin American Statesman.

The evidence that attitudes now closely associated with allegiance to Trump existed among GOP partisans long before they jumped at the opportunity to support his full-throated articulation both explains Republican politicians’ scrambling to reposition themselves in the wake of Trump’s exit and provides signs of what we can expect in Texas. The dead-ender support of Trump among so many Texas Republicans — commonly marked by only cursory condemnation (if at all) of the January 6 U.S. Capitol riot and Trump’s support of it — is the most clear illustration yet of how deeply embedded these impulses are in the Republican Party. The acquiescence of leaders like former Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and a minority of Republicans in both caucuses to trying Trump in the Senate isn’t mainly a sign of Republican rejection of Trump’s appeals to the anti-democratic impulses he has activated in their party. Rather, it shows that they still feel inclined to cloak their willingness to play to the reactionary members of their coalition who they need in order to maintain competitiveness both in their party primaries and nationally. This remains a necessity even if it is clearly in their self-interest to purge Trump himself from the party in the wake of his election loss, his embarrassing and destructive handling of that loss, and his impact on the party’s losses in the Georgia special elections that cost Republicans their majority in the U.S. Senate.

This tightrope walk underlines how central the anti-constitutional forces in the GOP remain for the Republican elected officials who have outlasted Trump. The ex-president’s revanchist appeals to nativism, white aggrievement (particularly among white men), and suspicion of democratic institutions and practices will continue to hold political currency. They are of particular salience in an increasingly competitive but still Republican Texas, where these forces are granted a veto by leadership that can’t even muster the expedient facade that McConnell and his few allies have managed as they consider purging Trump.

McConnell has room to play rope-a-dope with the Democrats and decide at the last minute either to save Trump from conviction, or, finally, to turn on the former President based on a clear cost-benefit analysis of Trump’s declining political value to national Republicans.

National Republicans effectively banishing Trump – stripped of the ability to run for office and facing significant financial and legal jeopardy as well as advancing age – would serve most Texas Republicans well. Virtually all statewide Republican office holders achieved their own level of success accommodating (if not mobilizing) the forces that would later be branded Trumpism, and they did so long before Trump was an electoral force. Given Trump’s current standing, they can do so again more easily without him.

However quickly the Texas GOP can turn to acting as though the last four years never happened, the threat of internal conflicts fueled by the forces Trump tapped into remain. Trump has inflamed internal divisions, and his unreserved willingness to tap into the party’s most anti-democratic currents has had a demonstration effect that has re-energized fringe forces that seemed subdued after the 2018 elections. Allen West’s ongoing provocations and Dan Patrick’s continued presence and fortification within a largely supine Republican caucus in the Texas Senate are recent examples. The potential for internal conflict notwithstanding, with Democrats running the federal government and the GOP in charge of redistricting, there is a lot of potential for the GOP to manage the flames that Trump fanned before his own self-immolation. Division is nothing new for Texas Republicans, nor is using immigration, cultural politics and a Democrat-led federal government to quell divisions and redirect hostilities.

As omnipresent as Trump has been in Republican politics, Biden had only barely taken the oath of office when Texas Republicans were already demonstrating an ability to pivot back to the playbook that served them well prior to Trump’s rise. Land Commissioner George P. Bush was early out of the gate, tweeting about “fighting for Texas values” and combatting “left-wing plans” to “put identity politics first.” Attorney General Ken Paxton followed on later in the day, pledging to “fight against the many unconstitutional and illegal actions that the new administration will take.” For his part, Governor Greg Abbott stayed above the fray, as he has for most of the turmoil of the last two weeks, choosing instead to comment on the homeless problem in Austin, then later Tweeting a fairly straightforward congratulatory message. By the next day, the Governor was holding a public event emphasizing a criminal justice reform agenda based on enabling the state to punish cities who reduce their policing budgets and carrying out bail reform. The echoes of the cries for law and order that the president trumpeted in the Fall were there, but with nary a mention of the man who led the party for the last four years. While some might see the arrival of the post-Trump era as a time of reckoning for the Texas GOP, it’s more aptly seen as a return to familiar territory.