How Did Beto O’Rourke Really Perform in the Democratic Primary Election?

After several months of breathless coverage of Beto O’Rourke’s campaign for the Democratic nomination to challenge incumbent Republican Senator Ted Cruz, O’Rourke’s easy victory with 62 percent of the vote brought forth widespread sighs of disappointment from many of the same reporters and partisans responsible for inflating expectations of his performance. The national press has moved on for now, but this all-too-familiar story of building sky-high expectations then blaming the candidate and/or his party when these expectations are disappointed still begs for some explanation. Was the disappointment in O’Rourke’s performance warranted? Even a preliminary look at data from the campaign and election suggests it isn’t.

O’Rourke, widely hailed as the most well-known and politically talented Democrat running in Texas this year, has increasingly led many partisans to once again envisage this as the year that Democrats break their decades-long drought and finally start to “turn Texas blue.” National and state reporters followed suit – with pro-forma hedging, to be sure – leading to a flood of national coverage often focused as much on the expectations as on the actual fundamentals of the task before O’Rourke. Inevitably, the headlines hailed O’Rourke’s coming in terms that amplified Democratic hopes.

Until, that is, two unknown candidates, Sema Hernandez and Edward Kimbrough, garnered almost 40 percent of the Democratic primary vote. In the wake of actual voting, O’Rourke’s 62 percent was taken as a signal of trouble ahead – as if his odds hadn’t already been long on day one. But what might an examination of O’Rourke’s performance look like absent wishful thinking, echo-chamber reporting, or both? Below, I look at five questions and some data driven evaluations of O’Rourke’s primary results, finding that assertions of his underperformance are both overstated, and miss some significant positives for the El Paso native to build on heading into November. He’s still a long shot, but evaluating his primary performance based on poorly estimated benchmarks leads to the mistake of missing the progress he’s made.

Is 62 percent a bad performance?

It’s not nearly so grim in the context of past Democratic performances. Looking back at Democratic Primary Elections for Senator and Governor from 2000 to 2018, O’Rourke’s 61.79 percent is the fourth highest vote share on the list, and the highest of any Democratic Senate candidate over that time period. Additionally, O’Rourke’s 641,337 votes is second only to Rick Noriega’s 1,110,579 in the 2008 Democratic primary, which saw record turnout fueled by the race between Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. O’Rourke received more votes himself than all votes cast for any Democrat in Wendy Davis’ 2014 Democratic Primary.

| Year | Race | Winner (Plurality) | Percent | Votes | Total Candidates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | GOV | Davis | 78.08 | 432,595 | 2 |

| 2010 | GOV | White | 76.04 | 517,487 | 7 |

| 2006 | GOV | Bell | 63.87 | 324,869 | 3 |

| 2018 | SEN | O'Rourke | 61.79 | 641,337 | 3 |

| 2002 | GOV | Sanchez | 60.73 | 609,383 | 4 |

| 2008 | SEN | Noriega | 51.91 | 1,110,579 | 4 |

| 2014 | SEN | Alameel | 47.04 | 239,914 | 5 |

| 2006 | SEN | Radnofsky | 43.09 | 215,776 | 3 |

| 2018 | GOV | Valdez | 42.89 | 436,666 | 9 |

| 2000 | SEN | Kelly | 35.68 | 220,531 | 5 |

| 2012 | SEN | Sadler | 35.13 | 174,772 | 4 |

| 2002 | SEN | Morales | 33.21 | 317,048 | 5 |

As long as we’re talking about it, how does O’Rourke compare to Davis?

A slightly more nuanced version of the criticism of O’Rourke might point to Wendy Davis’ ceding 22 percent of the primary vote to Ray Madrigal in 2014 as a signal of Davis-like trouble ahead. However, this ignores Davis’ subsequent campaign, Greg Abbott’s built in advantage of running as a Republican in a state that overwhelmingly favors Republicans, and the fact that 2014 turned out to be a bad year for Democratic candidates everywhere.

It seems hard not to compare O’Rourke to Davis though, as both of their candidacies were met with such fanfare. But, as already mentioned, O’Rourke received more votes individually than all votes cast in Davis’ Democratic Primary, while also facing an additional opponent.

On the other side of the ledger, Davis won a majority in 205 counties compared to 113 counties for O’Rourke. While this may seem to favor the common interpretation of O’Rourke’s underperformance, remember that Davis achieved broad statewide name recognition early – an unexpected turn of events that actually spurred her candidacy. In February of 2014, according to University of Texas/Texas Tribune Polling, 70 percent of Democrats held a favorable view of Wendy Davis, with 26 percent unable to offer an opinion – positive or negative. In February of 2018, only 53 percent of Democrats held a favorable view of O’Rourke, with 43 percent unable to offer an opinion. If you use their favorability ratings as a baseline, both candidates exceeded expectations by receiving their vote shares of 78 and 62 percent.

While most observers have been quick to admit that O’Rourke started out and remains largely unknown (though he’s made some progress), few seem to have incorporated this fact into their expectations about his performance. Instead, the focus has been on the contrast between his performance and the glowing national coverage O’Rourke has received in publications like The New York Times, The Washington Post, Vanity Fair, Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Spin, New York Magazine, and Mother Jones. The sobering conclusion from election night could just as easily have been that the mere presence of national coverage does nothing to negate O’Rourke’s low name ID, and just like the old saw that yard signs don’t vote, national coverage in high brow publications is not a stand-in for actual campaign work – something O’Rourke clearly knows.

But those vote-by-county maps sure make it look like Beto underperformed, don’t they?

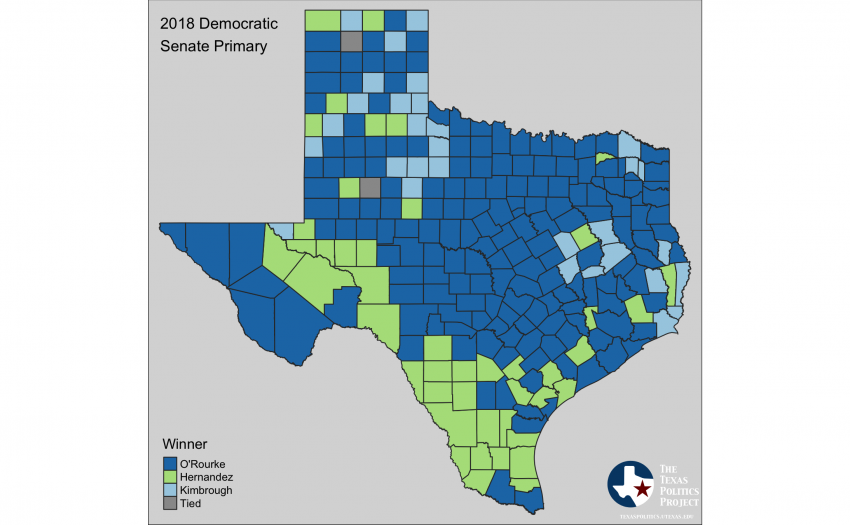

Well, they are only bad news if you don’t think about it more. Herein lies a big problem with presenting win/loss election results in county maps: it overstates the role of counties in elections. There’s no Electoral College-like prize for winning the most counties, and voters aren’t evenly distributed across the state’s 254 counties, so just counting counties won and lost (especially by glancing at a map) is misleading.

In this case, Sema Hernandez won a majority of the votes in only 15 counties, but those counties only accounted for 26,560 total Democratic primary voters – a meager 2.6 percent of all the votes cast. In contrast, O’Rourke got over 50 percent in 113 counties that accounted for 854,798 Democratic primary voters and 82 percent of all votes cast.

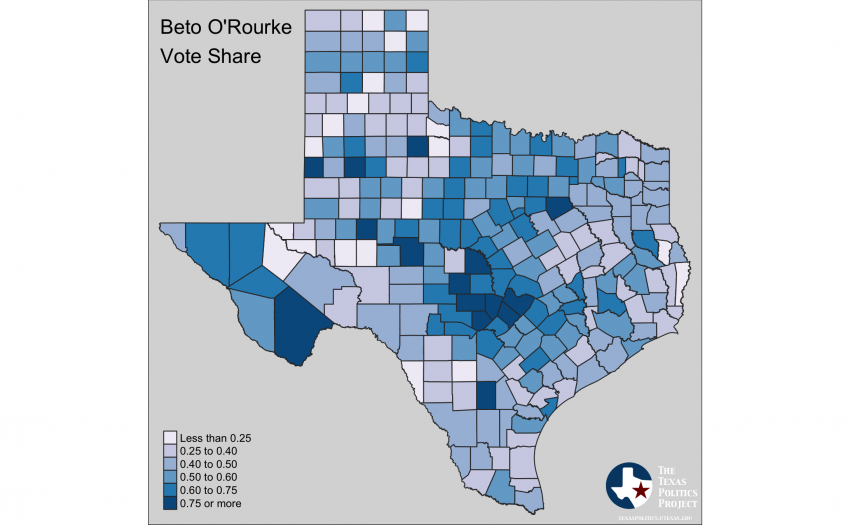

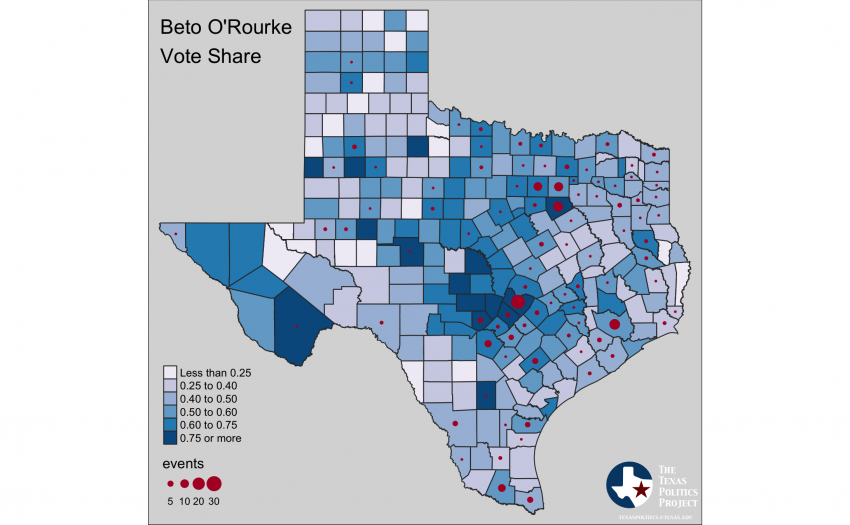

Looked at regionally, one can see that O’Rourke performed strongly in his native El Paso, and in most of the major metroplexes save (maybe) Houston. While one might wonder why Beto’s performance in Houston looks somewhat underwhelming in the map below, it does raise the question of what impact, if any, displacement caused by Hurricane Harvey could have had on voting in this region? I don’t have an answer for that, and it’s also possible that O’Rourke could or should have performed better in and around Harris County. While this may have been a problem in the primary, residential displacement aside, there’s no reason to think that O’Rourke will have trouble motivating Harris County Democrats come November, as this has been one of the areas in the state where Democrats have been making the most gains over the last few election cycles.

Does O’Rourke losing those counties mean he has a problem connecting with voters?

In short, the answer appears to be no. Looking at O’Rourke’s campaign events as advertised on his campaign facebook page between September 1st, 2017 and March 6, 2018, Beto performed well in the places where he actually campaigned – and the more he campaigned in those areas, the better he appears to have done. In counties O’Rourke failed to visit, he received 45 percent of the vote on average; he received 53 percent in those he visited 1 to 3 times, 58 percent in those he visited 4 or 5 times, and 67 percent in those counties that he visited 5 or more times.* For a candidate who is largely unknown, not running any television ads, and saving his resources for the Fall, this is a pretty good start that suggests his campaign work is paying off.

Does Beto have a Hispanic problem then?

This was a common question in response to the pattern in the county-level results, but looking at those same campaign events, it’s clear that he didn’t spend very much time on the border. Out of 230 total events, only 3 took place in the 26 counties completely encompassed by Congressional District 23 (which spans almost the entire length of the border), and only 13 in the four counties that traditionally make up what people refer to as the Rio Grande Valley (Hidalgo, Cameron, Willacy, and Starr). And not surprisingly, when examined side-by-side next to a map of the Districts Sema Hernandez won, a plausible story emerges about how an underfunded Hispanic candidate could capitalize against someone everyone expected to dominate in an area in which Hispanics account for approximately 70 percent of the population (in CD-23).

While not trying can definitely be a problem, real or perceived, it’s not something that should be over interpreted as reflective of a fatal flaw in O’Rourke’s appeal to Democratic voters in general, or Hispanics in particular.

In brief, here’s a case for why we shouldn’t expect O’Rourke to have spent much time on the border, nor, for that matter, to compete there in November. First, O’Rourke is running a general election strategy that looks to trade resources (time, money, campaign labor) for votes. So far, his campaign appears to be focussing on increasing turnout in highly Democratic areas likely to be mobilized by President Trump, with the added bonus of a limited potential to countermobilize the limited number of Republican voters in those areas. Second, his campaign appears to be visiting far-off Republican enclaves where he might narrow the gap in November. O’Rourke knows that there are Democratic voters living in these overwhelmingly Republican areas, but no one has paid much, or any, attention to them for a long time. By simply showing up, there’s a high likelihood that those voters may turn out in November (even if they might want to avoid outing themselves to their Republican neighbors in March). In each of these types of areas – those lopsided in their support of one of the parties – O’Rourke is looking to move his vote share by 5 to 10 points, from, for example, 70 to 75 percent or 15 to 20 percent.

The border fits neither of these descriptions, particularly the big chunk of it in Congressional District 23, historically the most competitive congressional district in the state. Whether O’Rourke campaigns there or not, the most likely outcome is an approximate split of the voters in an extremely competitive district in which he’ll have to spend more resources per vote in the general election campaign than makes sense given the likely outcome. CD-23 also has a number of other considerations that we might expect kept O’Rourke away during much of the primary. First, the voters are extremely spread out, making it hard to reach a large number of them with any single event and few major media markets. But more importantly, national organizations on both sides will be pouring resources into this district (some of the very limited resources any Texas Democrats are likely to receive from the party’s national campaign entities), so why should O’Rourke?

Laying out a case for why O’Rourke may have performed adequately, contrary to popular interpretations, is not the same thing as saying that O’Rourke will beat Senator Cruz in the Fall or that he’ll even perform very well. But before accepting that O’Rourke has already failed to deliver on the promise of his candidacy – as promoted by many of the same people who now lament his fall – seems unjustified at this point given the available data, and in particular, the context and strategy of his campaign in March of an election year.

* This may very well be endogenous. In other words, O'Rourke may have been campaigning in the locations in which he suspected that he already had the greatest strength, or, put a slightly different way, where his message was most likely to be well received.