Perceptions of Threat to White Masculinity and COVID-19 in Texas

Polling at both the national level and in Texas have increasingly shown partisan differences in attitudes toward the COVID-19 pandemic and in peoples’ reported behaviors in response to it. But an analysis of data in the June 2020 University of Texas/Texas Politics Project poll finds evidence of another, potentially surprising political profile distinct from party in COVID responses: Perceptions of threat to White masculinity. The data and discussion that follows demonstrate a strong linkage between the perception of a threat to White masculinity and attitudes toward the coronavirus pandemic. In short: the more an individual believes in the existence of a threat to White masculinity, the more likely that person is to downplay the severity of the virus, to believe it will be resolved quickly, to focus more on the economic than human harm, and is less willing to take part in private activities to stop the spread of the virus.

Several reports have identified a gender gap in perceptions of the danger of the novel coronavirus, including in Texas. Nations with female leadership have been applauded for their reactions to the virus, while male leaders, especially those who applaud traditional masculinity, have been reluctant to act decisively and, in some cases, have downplayed the dangers of the virus. The United States is no outlier in this respect, as men have been found to be less concerned about the virus and have been more likely to express opposition to precautionary behaviors, in particular, wearing a mask.

Following the lead of President Trump and Vice President Pence, who have both been reluctant mask wearers, male Republican leaders and their supporters have expressed a range of reactions from reluctance to disdain for mask wearing along with other precautionary measures. Many critics have lambasted the President and other Republican leaders for promoting a dangerous form of masculinity. However, they did not create this form of masculinity, they simply tapped into an ideology that has permeated the American consciousness. An ideology that has become more relevant — and open to criticism — in the face of widespread calls for social change. This ideology frames White masculinity as the historical ideal for America and argues that the nation’s problems stem from either the increased prominence of racial minorities and women in the gender-race hierarchy, or the demotion of White men as the natural leaders of the nation.

Perceived threat to White masculinity

Over the past several decades, scholars have directed their attention to the phenomena of increasing angst among White men as that group sees their prominence in American society diminish. Historically, the ideal American was viewed as both White and male. White men, specifically heterosexual White men, were seen as the group that led nation through the wilderness, civilizing its land (and its heathen inhabitants). These men showed no weakness, controlled their environment, and took swift action against those who would disturb the peace they created. In popular culture, White men, such as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood, were the heroes who put down the barbaric Native Americans or patrolled the city streets putting an end to the terror caused by violent, uncontrolled minorities. The most notorious example of how the media portrayed White men as heroes was D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, in which the Klu Klux Klan rode in to save the nation, and White women in particular, from the evils of freed Blacks.

After many decades, the societal repercussions of the civil rights, feminist, and LBGTQIA movements have eroded that image. Heterosexual White men are no longer, de facto, viewed as the epitome of American greatness. Instead and increasingly, they are viewed as a major part of its problem(s). There have been numerous attempts to stop this erosion, such as President Reagan’s 1984 “Morning in America” speech. In that speech, Reagan argued the nation was awakening from the nightmarish turmoil of the 1960’s and 70’s to a new day where traditional positions (read: hierarchies) were restored and maintained. However, despite these attempts, the nation has continued to face the threat of an end to the prominence of White masculinity over the past several decades, most recently with the election of the country’s first Black president followed by the first major party nomination of a woman for the presidency, followed by the nomination of the first black and Asian American woman to a major party presidential ticket. Along with new images of who can be president, the nation has witnessed the first woman serve as Speaker of the House, openly gay men and women take leadership positions in Congress, and a Latina nominated to the Supreme Court. These recent challenges to White, male hegemony also coincided with the Black Lives Matter movement, a national call to confront sexual violence against women in the #MeToo movement, and the recognition of same sex marriage as a legal right. Further, the diminishing economic opportunities for White men, especially those without a college education, further threatened their status as the American ideal.

The presence of so many examples of this ideology, extending historically into the present, serves as the impetus for the creation of a White masculinity threat index designed to capture the extent to which citizens believe that White men are a subjugated group. The measure ranges from zero to one, where zero indicates a respondent believes Whites and men are discriminated against at lower rate than Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, women, gays and people who identify as transgender. A score of one indicates the respondent believes Whites and men are discriminated against at higher rates than Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, women, gays, and people who identify as transgender. The index was constructed using survey responses, etc. Simply put, the higher the index rating - the nearer an individual or group gets to 1.0 - the higher their perception of threats to White masculinity.

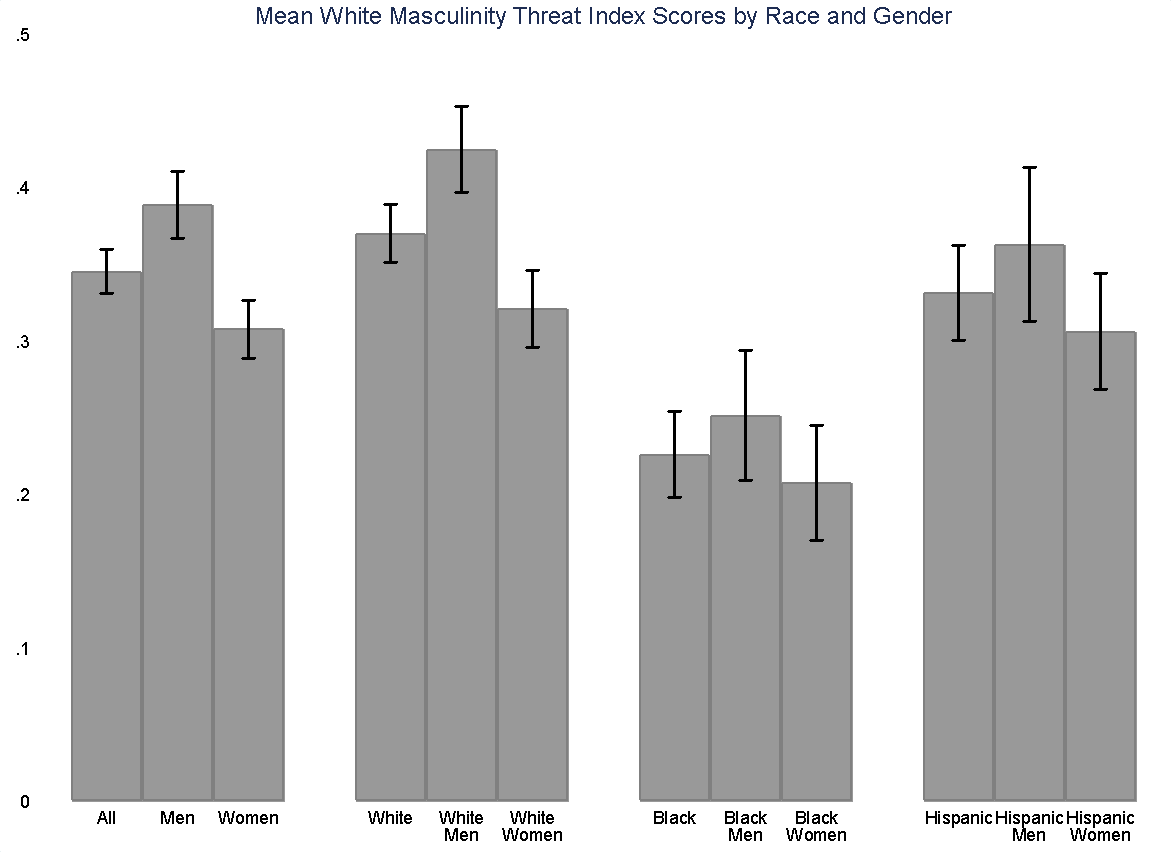

As Figure 1 demonstrates, White men score the highest (.44) on this index, followed by Hispanic men (.41), White women (.35), Hispanic women (.33), Black men (.26), and, finally, Black women (.22). White and Hispanic men score significantly higher on the index than the other groups, while White and Hispanic women score significantly higher than Black men and women (limits in sample size, unfortunately, foreclose the possibility of including Asian men and women in this analysis).1

Figure 1

In order to simplify the analysis and provide clarity to the reader, respondents were categorized based on where their index score. Those who scored in the bottom 25th percentile were categorized as low in their White masculinity threat, those with scores between the 25th and 75th percentile were grouped in the mid category, while those above the 75th percentile were classified as high in their White masculinity threat.

As Figure 2 shows, more than a third of White men were classified based on their responses as high in White masculinity threat, compared to only a quarter of White women and Hispanic men. Less than 5% of Black men and women are in the high category with more than a third of Black women and more than a quarter of Black men in the low category.

Looked at by age, slightly more than a tenth of those between the ages of 18 and 34 are in the high category, compared with more than a third of those 65 or older.

Education might be considered a plausible candidate for influencing where one scores on this index., There are no substantive differences in the percentage of those in the high category by education, but differences do appear in the low threat category. Slightly less than a third of the college educated are in the low category, compared to a sixth of those with a high school education or less.

Finally, and maybe surprisingly, the analysis shows little difference when it comes to income levels, as about a quarter of those with a household income of less than $30,000 and those earning $120,000 or more are in the low and high threat categories, respectively.

Figure 2

Moving from demographics to politics, Figure 3 demonstrates this ideology is associated with identifying with the Republican Party and positive evaluations of Republican officials at the national and state level. We find half of those who identify as a Democrat are in the low category, while slightly less than half are in the mid category and 3% are in the high category. Among independents, 15% are in the low category, while more than half are in the mid category and more than a quarter are in the high category. Republicans appear to be a direct juxtaposition to Democrats as 4% are in the low category, half are in the mid category.

This affinity for the Republican Party is also present in the evaluation of President Trump and state officials. Of those who disapprove of President Trump’s job performance, more than 97% are in the low are mid category. Only 3.5% of those who disapprove of the president’s job performance are in the high category. For those who approve of his job performance slightly 1% are in the low category, while 49% are in the mid category and 50% are in the high category. The evaluation of Governor Abbott, Lt. Governor Patrick, and Senators Cruz and Cornyn show a similar pattern as those in the low category constitute almost half of Texans indicating that they disapprove of their job performance, while Close to half of those in the high category constitute close to half of those indicating they approve of their job performance.

These results demonstrate a consistent partisan bias among those at the polar ends of the measure: The Democrats have a core base among those who reject the idea of a threat to White masculinity, while Republicans have a base in those who embrace this belief. This is further reflected in the disapproval and approval of national and state leaders' job performance.

Figure 3

Moving from providing a social and political image of who adheres to the belief of White masculinity, Figures 4 and 5 demonstrate the attitudes of those in each category of White masculinity threat in relation to recent events and groups. When asked whether increasing racial and ethnic diversity in Texas is a cause for optimism or a cause for concern, more than three-fourths (79.6%) of those in the low threat category said that they see the state’s changing demographics as a cause for optimism, compared to less than a third (31.5%) in the high category. More than two-thirds of those in the high threat category (68.5%) view increasing diversity as a cause for concern compared to a fifth of those in the low category (20.4%).

Figure 4

The respondents were also asked their interpretation of the recent killings of Blacks while in the custody of police. In particular, whether these killings are isolated incidents, or a sign of broader problems. The views of those in the low and high threat categories are mirror opposites, almost all of those in the low threat category (94.36%) believe these deaths are a sign of broader problems, while almost all of those in the high threat category (94.71%) view these deaths as isolated incidents.

Figure 5

In fitting with these assessments of fatal encounters between Black people and law enforcement, Figure 6 demonstrates drastic differences in perceptions of the protests in response to George Floyd’s death, the Black Lives Matter movement, and the police. More than half of those in the low threat category hold a “very favorable” opinion of the protests and Blacks Lives Matter, while more than two-thirds of those in the high threat category hold “very unfavorable” opinions of the recent protests and the Black Lives Matter movement. Regarding the police, more than half of those in the low threat category have a “very” or “somewhat unfavorable” view of the police, while close to 90% of those in the high category have a “somewhat” or “very favorable” opinion of the police.

Figure 6

Perceived White masculinity threat and views of the pandemic

Given the nature of White masculinity threat, these results are not surprising and should be expected among most observers. What might surprise some is the extent to which this threat also appears to relate to attitudes and personal behaviors relevant to attempts to contain the coronavirus. As Table One demonstrates, a comparison of coronavirus-related attitudes among the three White masculinity threat categories finds stark differences in the Texas electorate. Almost all of those in the low and mid categories believe COVID-19 is either a “crisis” or a “serious problem”. Further, the majority of respondents in each of these categories believe it is a crisis (as opposed to a mere serious problem). Less than two thirds of those in the high category believe it is a crisis or serious problem, while less than a fifth believe it is a “crisis”.

There is a similar difference in levels of concern about the spread of the coronavirus in their communities and contracting it themselves or knowing someone who contracts it. Close to half of Texans report being “extremely” or “very concerned” about its spread in their community. Approximately 80% of those in the low White masculinity threat category express the same level of concern, while close to half of those in the mid category are “extremely” or “very concerned”. Among those who are high on the White masculinity threat index, approximately 15% said that they are “extremely” or “very concerned”, while more than half state that they are “not very”, or “not at all” concerned.

Concern about personally contracting the virus or knowing someone who gets infected follow similar patterns. Close to half of Texans indicate that they are “extremely” or “very concerned”, while more than three-fourths of those in the low threat category and slightly more than half of those in the mid category express this level of concern. Among those in the high White masculinity threat category, approximately 15% report being “extremely” or “very concerned” while the majority expressed they are either “not very concerned” or “not concerned at all”.

| Item and Responses | White Masculinity Threat | |||

| Severity of COVID-19 | All | Low | Medium | High |

| A significant crisis | 56.6 | 94.2 | 60.8 | 18.7 |

| A serious problem but not a crisis | 28.6 | 4.6 | 30.1 | 45.8 |

| A minor problem | 9.8 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 27.3 |

| Not a problem at all | 3.6 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 8.2 |

| Concern for spread of coronavirus in community | ||||

| Extremely or Very concerned | 46.8 | 80.4 | 48.6 | 15.5 |

| Somewhat concerned | 26.1 | 18.0 | 27.8 | 29.0 |

| Not very or Not at all concerned | 25.9 | 1.3 | 22.2 | 55.3 |

| Concern about self or someone know getting infected with coronavirus | ||||

| Extremely or Very concerned | 47.8 | 77.3 | 52.5 | 16.4 |

| Somewhat concerned | 23.9 | 18.1 | 22.4 | 26.6 |

| Not very or Not at all concerned | 27.0 | 4.6 | 23.5 | 56.9 |

Interestingly, White masculinity threat also appears to be related to how long Texans believe the virus will continue to interrupt activities. As of June, slightly more than one-fifth of Texans believed that the virus had already been contained or would be contained in the next few weeks. Slightly more than one-fifth believed it would be contained in the next few months, while slightly more than a quarter believed it would be contained in the next year, and another quarter believed it would be contained in more than a year. A little more than 3% of Texans believe it will never be contained. A comparison of the categories finds that no matter how much a respondent perceives a threat to White masculinity very few believe the virus will never be contained. However, there are stark differences regarding when it will be contained. More than 80% of those in the low White masculinity threat category believed the virus would be contained in a year or more. The majority of those in the mid category believed it would be contained in a year or more, while only a quarter believe it will be contained in the next few months. Among those in the high category, more than 40% believed that the virus had already been contained or would be contained in the next few weeks, with an additional quarter who believed it would be contained in the next few months.

| White Masculinity Threat | ||||

| Responses | All | Low | Medium | High |

| It is already | 11.6 | 1.6 | 7.6 | 27.2 |

| In the next few weeks | 9.2 | 1.5 | 9.6 | 15.3 |

| In the next few months | 21.6 | 10.2 | 24.2 | 27.4 |

| In the next year | 25.8 | 43.9 | 26.7 | 9.6 |

| Never | 3.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.3 |

Throughout the period of active government engagement with the coronavirus there have been concerns about how, and how much, restricting movement and shutting down businesses would harm the local, state, and national economy. Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick pleaded for the reopening of businesses to protect the economy, arguing that grandparents, like himself, would be willing to sacrifice their health (and even their lives) to save the American economy for their grandchildren. However, a majority of Texans expressed a willingness to help control the spread of the virus, even if containment comes at the expense of the economy. The vast majority of those in the low category and the majority of those in the mid category expressed support for controlling the spread of the virus even if it harms the economy. In stark contrast, 80% of those in the high White masculinity threat category believed that priority should be placed on helping the economy, even if those efforts hurt attempts to control the spread of the virus.

| White Masculinity Threat | ||||

| Responses | All | Low | Medium | High |

| Trying to help control the spread of the coronavirus, even if it hurts the economy | 53.5 | 88.9 | 58.9 | 11.3 |

| Trying to help the economy, even if it hurts efforts to control the spread of the virus | 37.7 | 5.9 | 32.4 | 80.6 |

Perceived White masculinity threat and reported behavioral responses to recommended anti-pandemic measures

Along with concerns about the threat of the virus, the June survey asked questions related to individual actions Texans are willing to take in an effort to protect themselves while helping to control the spread of the virus. Overall, Texans, no matter where they fall on the White masculinity threat index, demonstrated a willingness to comply with public health warnings. At least three-fourths of Texans reported frequent hand washing, avoiding touching their face, avoiding large groups, avoiding people as much as possible, and wearing a mask when in contact with people outside of their household.

Even with this high level of compliance, those in the high threat category remain laggards, with close to 80% reporting washing their hands more frequently, slightly less than three-fourths reporting staying away from large groups, and close to two-thirds avoiding touching their face. However, we find that less than two-thirds reported avoiding people as much as possible or wearing a mask. A high percentage of those in the mid category are also engaging in these activities, but not to the same extent as those in the low category. Almost all the respondents in the low threat category report increased hand washing, staying away from large groups, avoiding people, and wearing a mask. The mask controversy, in particular, has been a national issue with President Trump and other public officials openly questioning the benefits or necessity of mask wearing. This has led to numerous confrontations between citizens and government, as well as shoppers and retail outlets as a small, but significant, portion of the public has resisted calls for widespread public mask wearing. This finding indicates that these visceral reactions to mask wearing are, interestingly, but not incomprehensibly, linked to perceived threats to White masculinity.

| White Masculinity Threat | ||||

| Measures | All | Low | Medium | High |

| Washing hands more | 89.8 | 98.5 | 91.1 | 79.8 |

| Avoiding touching your face | 75.0 | 85.4 | 74.9 | 66.0 |

| Staying away from large groups | 88.2 | 97.8 | 91.2 | 72.3 |

| Avoiding other people as much as possible | 80.2 | 95.6 | 83.7 | 60.0 |

| Wearing a mask when in close contact with people outside your household | 80.6 | 98.1 | 82.6 | 62.6 |

The data also demonstrates this link when examining the extent to which Texans are staying home. Very few Texans, regardless of perceptions of threat to White masculinity, report not leaving their homes at all; however, there are differences in other behaviors. Close to a fifth of Texans report living normally during the pandemic. This is strongly influenced by those in the high White masculinity threat category, with close to 40% of this group reporting no substantial change in their behaviors. For those in the low threat category, only 5% report this, while approximately one-sixth of those in the mid category report this behavior.

| White Masculinity Threat | ||||

| Responses | All | Low | Medium | High |

| Living normally, coming and going as usual | 19.3 | 5.0 | 15.7 | 39.9 |

| Still leaving my residence, but being careful when I do | 41.0 | 29.0 | 47.1 | 43.3 |

| Only leaving my residence when I absolutely have to | 37.2 | 63.0 | 34.5 | 16.8 |

| Not leaving home | 2.6 | 2.9 | 2.7 | 0.0 |

When asked about their willingness to comply with certain actions if they were infected or came into contact with someone who was infected, we find greater willingness to comply with activities done in the privacy of one’s own home and lower compliance with activities associated with government monitoring. Close to three-fourths of Texans are willing to quarantine themselves for 14 days if they are notified they came in contact with someone who tested positive for the virus or provide a list of people they have recently come into contact with if they contract the virus. Further, close to two-thirds are willing to take part in weekly testing to track the progression of the virus. The least supported activity is providing access to cell phone location data if tested positive. Less than half of Texans are willing to give up this level of privacy.

Comparing those at the three levels of perceived White masculinity threat, we find slightly more than half of those in the high threat category express a willingness to quarantine, compared to almost all of those in the low category and more than 80% of those in the mid category. Regarding providing a list of people they have come in contact with, less than half of those in the high category say they would comply, while more than 90% of those in the low category and three-fourths of those in the mid category would comply. Weekly testing finds a similar pattern, with less than half of those in the high category willing to participate in weekly testing. In contrast 90% of those in the low category and two-thirds of those in the mid category would submit to testing.

| White Masculinity Threat | ||||

| All | Low | Medium | High | |

| Agree to mandatory 14-day self-quarantine if you are notified that you came into contact with someone who tests positive | 76.1 | 94.1 | 81.5 | 52.7 |

| Provide a list of all the people you've recently come into contact with | 71.3 | 91.7 | 77.6 | 44.4 |

| Provide access to your cell phone location data if you test positive | 45.8 | 70.2 | 47.7 | 24.9 |

| Agree to weekly testing to track the progression of the coronavirus pandemic | 65.7 | 90.2 | 69.4 | 44.0 |

Finally, across all three of the categories, Texans are less likely to provide cell phone location data. A quarter of those in the high White masculinity threat category are willing to provide these data and less than half of those in the mid category are willing to do the same. What demonstrates the controversial nature of providing cell phone data is the relatively lower level of compliance among those in the low threat category. More than 90% of those in the low category were willing to take part in the other activities; however, slightly more than two-thirds are willing to provide cell phone location data.

These results indicate that the ideology of White masculinity threat offers an explanation for the divide amongst Texas regarding how to respond to the pandemic. Those who believe White men are not being subjugated are more likely to view the virus as a serious threat and are more willing to take extreme precautions to prevent its spread. In contrast, those who believe White masculinity is under attack downplay the severity of the virus and precautions. Further, they are more likely to endorse the idea society should return to normal functioning, even if these actions may increase the spread of the virus.

Given the partisan nature of the discussion of the virus and the partisan leanings of those who adhere to the ideology of White masculinity threat, some may believe this ideology is a proxy for some other attitude or identity, such as religiosity, partisanship, or attitudes toward President Trump. To address this, a multivariate analysis was performed that accounted for how religiosity (biblical literalism, religious tradition, and worship attendance), sociodemographic attributes (age, sex, income, education, race), political ideology, and partisanship impact attitudes toward the pandemic along with concerns about threats to White masculinity. The results find the relationship between White masculinity threat and responses to the pandemic hold. This indicates the ideology of White masculinity threat is not merely a product of some other social phenomenon, such as partisanship or the Trump presidency, but something that has a life of its own that the GOP and President Trump have been able to tap into.

Description of White masculinity threat index

The White masculinity threat index is an additive index comprised of relative perceived discrimination against Whites and men. The measure of relative discrimination against Whites is each respondent’s average perceived frequency discrimination against Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians subtracted from the percieved frequency of discrmination toward Whites. The measure of relative discrmination against men is a respondent’s average perceived frequency of discrimination against women, gays and lesbians, and transgenders subtracted from the perceived frequency of disrimination toward men. These relative discrimination scores were added together to create the White masculinity threat index. These two items have a strong positive correlation with a score of .66 or higher in the three polls these items were included (June 2015, February 2018, and June 2020). Further, the measure’s Cronbach’s alpha score is .80 or higher across each of these polls, indicating a high level of reliability.

Eric L. McDaniel is an associate professor in the Department of Government and a fellow of the Population Research Center and the Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis at the University of Texas. He is currently serving as a Public Religion Research Institute Public Fellow.

***

1 These items were also included in surveys conducted in June 2015 and February 2018. In 2015, White men had a mean score of .49, followed by White women (.39), Hispanic men (.35), Black men (.27), Hispanic Women (.27), and Black Women (.26). In 2018, the mean score for White men was .50, followed by White women (.37), Hispanic men (.36), Hispanic women (.27), Black men (.27), and Black women (.23)